It’s Dementia Awareness Month, so I thought this piece I wrote a few months back would be a fitting first blog entry…

My paternal grandmother is turning 96 in the coming weeks and has been in residential care for just over two years now. I can scarcely believe it. I’d never have imagined living to see the day when she went into care. It certainly wasn’t her choice. She’s bloody-minded and independent and doesn’t always play well with other kids. I’m only slightly less astonished that she is hurtling – or should I say wheelie-ing – towards 100. But she is a stubborn buggar, or should I say was.

On my last visit, she was feeling poorly and hadn’t made it past the bed covers. As I held her hands in my cold ones (it always amuses both of us that my hands are perennially chilly…she howls in mock horror with the jolt of them), she suddenly sat forward, looked me dead in the eye, and whispered urgently, conspiratorially, “Listen”… (In the intervening micro-seconds before the rest of her words tumbled out, I could hardly breathe with the anticipation of what she might be about to ask me.) …“Can you tell me if my mother is still alive, because sometimes I forget”. Oh dear, what to say.

The first time she spoke of my great grandmother (still) being alive, I nearly fell off my chair. It was an undeniable, brutal proof of the dementia that was taking hold. She asked me if I had seen her mother and I stumbled around the question thus: “No, have you”? When she lamented that “Mama” hadn’t bothered to visit her once since going into care, I inquired gently, “Do you miss her?”, to which she responded “Yes” (often her lips purse and she’s genuinely unsure). We talked some more about the “get-about” Mama had been and laughed at the audacity of it, with me escaping having to either confirm or deny the “truth” of matters. Later I would marvel with family that she hadn’t done the maths. If she were 95, then Mama would be 115! Another few months down the track, Grandma announced incredulously: “Do you know my mother is over 100”! Ever sharp, both of mind and tongue.

This time, however, I couldn’t wriggle so easily. You see, most days now I’m not even sure if she knows who I am. Let me be precise. She knows me. I call her “Grandma” (clue to being her granddaughter) and she feels me or knows me in an embodied way: I’m familiar, we have an easy rapport and she seems relieved that I’ve come. But she probably wouldn’t know my name (I dare not test her) and if I lined up close family members in front of her, I am confident she wouldn’t be able to tell who was connected to whom. Because the connections are being eroded from use over a long life, bleached by the sun, fading like ghosts. But though she might not be able to reliably recall my name, she has me pinned that I will always tell her the truth (I’m a stickler for the truth, because the alternative is usually infinitely more complex), even when she doesn’t want to hear it. So I gulped and answered honestly, but diffidently: “No, no Mama’s not with us anymore”. This seemed to confirm what she already suspected, as she looked at me, very still. I thought that was the end of the matter, but she pressed on, imploring, “But Bill’s still with us, isn’t he?” Bill was my grandfather, her husband, who died 15 years ago from health complications he’d endured since serving in Papua New Guinea during WWII. At this point the coward in me trumped the pedant and I offered the feeble consolation, “Yes, he is; he’s in our hearts”. Grandma continued to hold my gaze. She knew I’d copped out, but didn’t want to disappoint either of us by digging around for old bones. The conversation moved on.

When Grandma first went into care, great anxieties about dependency and loss of control over her own life, along with a discombobulating sense of dis-ease with her physical and social environment, were soon enough replaced with an almost palpable relief that she no longer had to bear the burden of looking after herself alone. At 90 odd, especially when you live alone with only a dog for constant company, just surviving comes with a certain level of physical and mental strain. Prior to going into care, she talked of being tired often. She had naps most days and still does. Without the burden of self-care, however, there was a noticeable upturn in her health and spirits. She looked brighter, put on a bit of needed weight, seemed happy to be surrounded by peers and the opportunity for a chat here and there. Her memory improved. She repeated herself less frequently and could keep up with current affairs involving the family and the world in general.

But then, this too changed, as the slow realisation dawned that she wasn’t going back home. That she didn’t even have a home anymore because it had been sold. That her current company held up a mirror to her growing infirmity and the slippery slope that is dementia and old age. All paths converge to one point, one end. She became frightened all over again. And with the strain of not having to look after herself gone, she did indeed slip downhill. She no longer needed to fight and keep her wits about her. Other residents were kind enough to let me know that her awareness of forgetting things and people was causing her distress and tears that she dare not show any of us. As Christmas approached, she made plans of baking her Christmas fruitcake, until she remembered she no longer had her own kitchen. Although I offered to do it with her at my place, we both knew she wasn’t up to it. She showed signs of dementia-related paranoia, constantly worried that staff were taking toothpaste from her bathroom. She asked the same questions over and over and over again. Actually I was grateful for the reprieve in having to initiate topics of conversation, struggling to explain and relate events that were fading in meaning and relevance to her. I am amazed at how you get at and around a subject by answering the same question over and over again, building up layers of understanding. Some days I conceded: “I can’t think of anything riveting to report, can you”? And we’d sit in silence, contented that words can’t convey everything anyway.

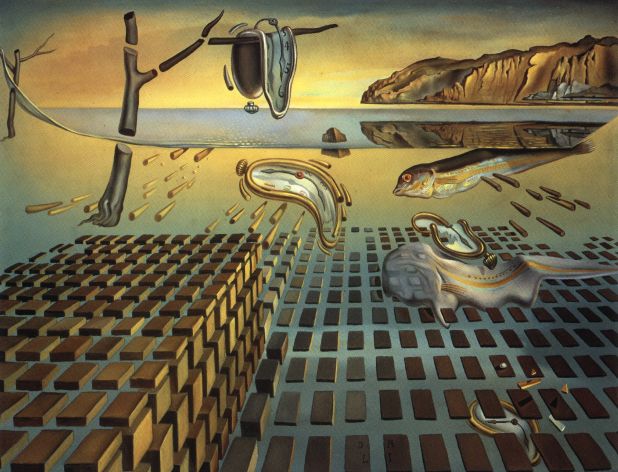

Time started to warp. Instead of being linear, it became circular. The line between reality and fantasy was also blurring. Other things went missing, like favourite cake tins from her (long-gone) kitchen. She had her wheelie up for sale. Like magic, she could shoot down a wormhole and be in Fitzroy, a little girl trying to cross Brunswick Street to see her father in his fruit shop. A repeated theme, she is often too afraid to venture across the busy road and returns, disappointed, her father tantalisingly out of reach. When my parents visit, she often inquires about my mother’s father, gone 10 years, and is mortified that they’ve apparently left the children – my brother and I – at home. When Mum assures her I am at home looking after my own children, sometimes the wires touch and a deduction is made; mostly there’s a quiet confusion. When my daughter visits, Grandma is always fascinated by how much she looks like my Mum! The penny drops, if for a moment. Mostly, she cannot tell me what she’s done five minutes previously and wouldn’t have a clue if she’s been on a morning outing. When she tells me she has been somewhere, her evidence is completely unreliable: Pa’s driven her down the line somewhere for lunch with a car load of ghosts. She also tells me he now supplies the grog for Happy Hour at the residence!

Her mother is omnipresent. There’s a theory that because early memories have been rehearsed more frequently and are therefore etched more deeply into the brain, these are the ones that are often returned to, especially as short-term memory begins to falter. There’s another theory that recall of attachment figures is an attempt to allay anxiety associated with the disorientation of dementia. Mum wonders if Grandma hears her parents calling from beyond, soothing her that life’s journey is coming to an end. She’s not sure Grandma is quite ready for it: She hasn’t made it back to her father. I do think she’s still playing out attachment issues and reveals quite a bit of ambivalence about the way she was mothered in particular. Grandma has been an important attachment figure in my own life, not always benevolent. She lost her brother in the war and the grief has plagued her all her life. Depression has been a frequent visitor. Hers was not a happy marriage, realising her mistake as she was (literally) about to walk down the aisle, her father resolute that it was too late to change her mind. Her two sons are locked in a war of their own, which started with her playing a game of favourites long ago. A truce seems very unlikely. She’s often been cross with my own father and I’ve challenged and argued with her since I could talk.

I spent a lot of time with my grandmother as a youngster. She taught me to sew – she was a brilliant and fastidious dressmaker and seamstress – and handed on a passion for baking. I know all my cuts of meat. I’ve often sought her counsel over matters of concern, like the time I had a dilemma about whether to attend a pool-party play date, initiated by a dad with unclear motives (promoting a friendship between our respective sons or seeing me in my bathers). She was ninety at the time and knew exactly what to do (politely say “nooooooo”….)! I’ve always been able to talk to her about anything. I understand that small things done for another with care and attention can be gifts of love. Like a beautifully made, well-cut sandwich. Like manicured nails and cuticles. Like a hand-stitched blanket. Like being present and being on time. Porridge with cream and sugar will always elicit rosy memories of childhood. Toasted cheese sandwiches and chocolate cake too. I often think about how the tables have turned in recent years, with the younger generation being more responsible for the older one than vice versa. It seems like I’ve been taking care of Grandma longer than she ever took care of me. I also see it as my duty; it’s my turn to do the nurturing. Despite her terrible hearing (hearing aids are imperfect at best, rendering telephone calls completely futile), I will never raise my voice, preferring to repeat myself until she understands. Nor will I infantilise her with a condescending (“sweety darling pet”) or sugar-coated tone. I’m clear of my place in the hierarchy and there’s not much that I will go through that she hasn’t already experienced.

Before going into care, we spoke frankly about what I should do if she had another “turn” overnight, possibly a minor heart attack at the time. We agreed that I wouldn’t report the incident to anyone, that she’d lived a good life and that it might be best to just “pop off”. Some days when I see her now, I pray that she will pop off quietly sooner rather than later. It’s not much of a life waiting at the gates. I don’t visit as often as I ought. Winter bugs and other contagious illnesses going through the household can keep me away, but mostly it’s the sadness of seeing her go further and further downhill. I cannot overstate, however, how personally important it has been for me to be brave enough to remain witness to the journey. Where once her anger and disapproval could shake me to the core (I know she told the neighbours when I disappointed her or refused to do as she wished, which was probably often), these days she’s far too frail, and wouldn’t remember anyway, to hold on to a grudge. Fantasies about her power have fallen away. A typical visit now involves me painting her nails (she often opts for the bright pink, although she can’t see it anyway) and the mutual imbibing of chocolate, followed by a hairbrush that lulls her to sleep. I smother her with kisses as I leave and tell her I miss her. It’s tactile and gentle and soothing for both of us. I’ll be devastated when she dies and I’ll always miss her. But I’ll also be okay with it. As she withdraws from the world, any past hurts also recede and a peace washes in about the inevitable. Life, like memory and imagination, is circular.

Beautiful writing Tan. I had a little tear in my eye at the end. She taught you a lot and that is evident. Your care and consideration of her is selfless and kind. It is how I think we all want to be treated towards the end of our lives. A real reminder of what is truly important.

Thanks Tan.

Michelle x

LikeLike

Thanks Mic! xox

LikeLike